Meanwhile in Ireland: mortgage arrears still growing

While everyone is talking about Grexit, and all eyes are looking at Spain, more and more Irish people find it hard to repay their mortgages, which is a very bad sign of the inexistence of any sustainable recover of the irish economy.

While everyone is talking about Grexit, and all eyes are looking at Spain, more and more Irish people find it hard to repay their mortgages, which is a very bad sign of the inexistence of any sustainable recover of the irish economy.

Despite congratulations speeches to Ireland, the country has still not fully recovered from the housing bubble bust that hit the country in 2008. If it were, household over-indebtedness should be on the path of a downsizing trend. But this is not the case: more and more irish people are finding themselves incapable of honoring their mortgage payements.

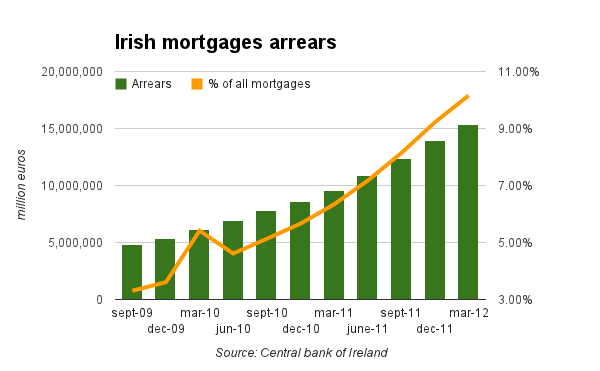

As a proof, data released last week by the central bank of Ireland reveals that mortgages in arrears (ie. mortgage not being repaid in full) are still increasing in the country. At end march 2012, at least 77.6k households failed to make their mortgage repayement in full or at the due date (more than 90 days delay). This represents roughly 15 bn euros of mortgages at risk and 10,1% of overall current mortgages contracts in Ireland.

Unfortunately, this trend is anything but new. For 3 years now, mortgage arrears have been growing by 10-12% quarterly, and are reaching a new peak every time:

From a closer look, we can see that arrears by 180+ days are ballooning, which means that the figures are likely to reveal a longer-term solvency issue of Irish household:

Another warning signal is that the total amount of outstanding mortgages has only decreased by 4,5% since 2010 while arrears have more than doubled by then. On top of that, a certain amount of mortgages were restructured without being in arrears. This specific cases represent 38,000 contracts since the beginning of the crisis.

Here the simple lesson that Ireland is teaching us: unless Ireland experience growth and a decrease of unemployment, there are very few chances for this phenomenon to swing. The more austerity you have, the more people lose purchasing power, the less they are likely to be able to repay their debts.

And the less people repay their debts, the more banks will be struggling to balance their accounts. As a result, unless some private investors pay the price for the risk they were granted for (which Ireland – under pressure of the ECB, refused to do), central banks and/or States (ie. taxpayers) will have to pump new money into them.

I hope there are some spanish policymakers in the classroom.

Picture ![]() Diana Parkhouse

Diana Parkhouse