The euro is futureless if it cannot survive the next recession

Or why EU politicians should worry more about the existential crisis of monetary policy in the Eurozone – and look at ‘helicopter money’.

Last week I attended an interesting panel session at the Bruegel Annual Meetings on “The Future of the euro from an Historical perspective” which featured MEP Sylvie Goulard, Romano Prodi, Joaquim Bitterlich and André Sapir as chair.

Funnily enough, it took only the last round of questions until someone made the observation that the panel didn’t discuss monetary policy at all, neither did it comment much on the role of the ECB.

In fact, the only moment when the topic of monetary policy came up was when Romano Prodi eloquently said that “the ECB can provide parachutes, but it cannot provide a plane. And we need a plane now”. Other speakers seemed to agree, basically praising the ECB for its commitment and effectiveness at saving the euro.

Those statements reflect rather well a general sentiment shared in the EU bubble: the ECB is doing a good job and should not be criticized. In Brussels, the ECB is often portrayed as the most effective EU institution, it is difficult to criticize it. What’s more, it’s the most federal institution of the EU, which is convenient from a federalist standpoint. A widely shared consensus is that the problem of the euro is mostly about the political and institutional framework surrounding the ECB, not its monetary policy.

In fact, one could even argue that challenging monetary policy could be perceived as a distraction from doing the ‘structural reforms’ that are supposedly needed in the eurozone. The last thing leaders want to do is to create an institutional conflict with the ECB.

From this viewpoint then, the ECB itself is neither the problem nor part of the solution.

The existential crisis of monetary policy

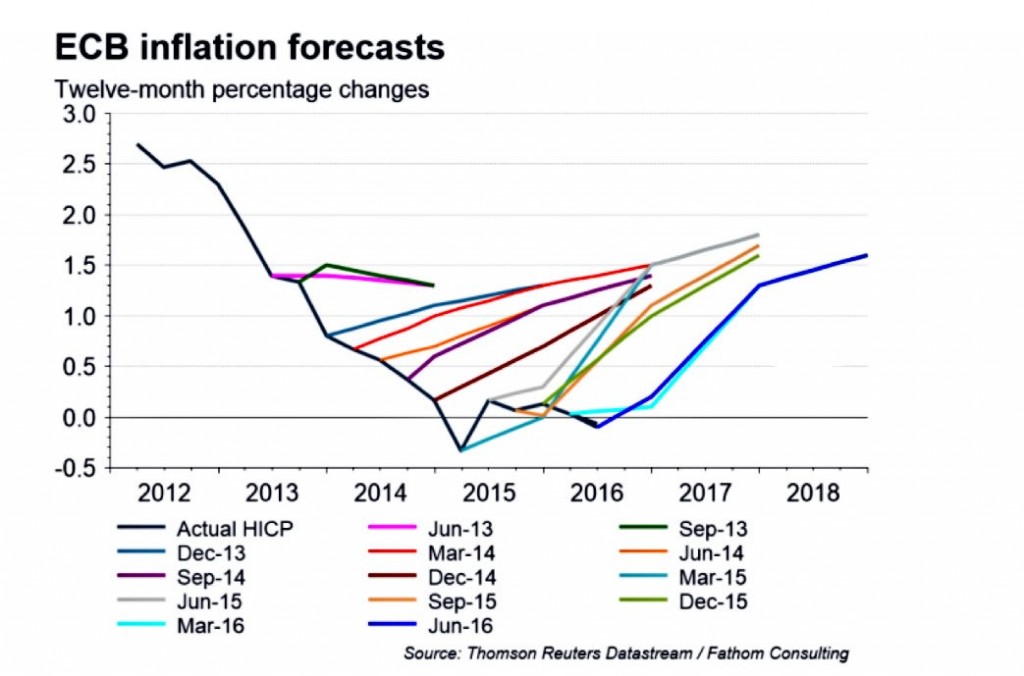

Yet, here we stand with the ECB having more than one trillion euros of bonds on its balance sheet but still being nowhere close to reaching its inflation target since 2013. Monetary policy is facing an existential crisis, but politicians seem not to care so much.

To be fair again, monetary policy is not a specific problem of the eurozone. Virtually all Western central banks are facing important challenges in the effectiveness of their monetary policy. Even if you consider that Quantitative easing was necessary (although this point is arguable: QE would have been necessary at the heart of the greek crisis but not so much in 2015), it is clear that more QE doesn’t help much anymore. Negative interest rates are counter-productive and punishing savers, raising rates could do even more harm. The single monetary policy transmission channel, the banking sector, is broken. Perhaps because the failure of monetary policy is not only happening in the eurozone, EU leaders do not pay so much attention to it.

Another reason is that the eurozone situation is made even more difficult due to the complexity of the crisis of EU governance and the fact that the monetary union has not yet been completed with significant budgetary capacity. Therefore politicians want to focus on those issues as opposed to looking at monetary policy itself.

Another ongoing trend is the growing consensus that monetary policy seems to be reaching its limits and now it’s up to politicians to do their job too. For example by doing more fiscal stimulus.

The problem is, no one except Germany seems to be in a position to being able to deliver such a stimulus, notably due to the infamous Fiscal and Stability pact – which essentially prohibits any type of significant fiscal stimulus right now. In that regard, it is to be welcomed that the EU Parliament is about to pass a report on the “budgetary capacity for the eurozone” with ideas such as turning the European Stability Mechanism into a sort of Eurozone treasury, which is already de facto issuing eurobonds.

I would usually say: “better late than never”. However, this time I’m afraid, this could come too late.

There is no contingency plan in the Eurozone

With the Chinese and Italian crisis looming, and all the various political risks in Europe with the rise of populism, there seems to be a shared sentiment that a single spark could bring us down again to a crisis.

If such an unfortunate event happened, what will be the plan then? Talks of long-term investment, ‘structural reforms’ and fiscal planning will suddenly become irrelevant, if not a complete distraction.

“Can we live five more years of uncertainty like we just did? No we cannot.” Romano Prodi said at the panel. He is right. The eurozone is already too traumatized by the catastrophic management of the greek crisis and its contagions. Markets will strongly react (ie. freak out) if circumstances deteriorate and if they have the sentiment that the ECB is not truly determined to do whatever it takes, or that it is clueless about what to do. There cannot be a long-term perspective for growth when there is a general feeling that the euro economy could collapse tomorrow.

Think of the EU as a homeless person. Being homeless entails so much stress every day, that everything goes wrong. You are so concerned and stressed about your next meal that you cannot make long term plans that would actually bring you out of your dire situation.

The state of the European Union is alarmingly similar: there is so much fear that things can go wrong again that the entire political and institutional is blocked. Frankly speaking: there is currently no contingency plan if the eurozone falls into recession. And perhaps this is one of the main problems right now.

Just like providing basic security to a homeless person is probably the best way to get this person back on track, the eurozone needs a contingency plan, to provide assurances that it cannot fall into recession again.

Monetary policy is the only reliable rescue plan

As it has been showed in the past, only monetary policy is capable of reacting swiftly to any unforeseen event of this sort. The reason is, it doesn’t get much for central bankers to have effective impact: merely a conference call and a well-written statement to the press can do the trick.

The ECB has a clear mandate: provide price stability, that is to say, prevent any deflation spiral from happening. And it has a lot of flexibility to achieve this mandate, as it has shown in the past.

Except this time the ECB’s set of conventional tools will be almost expired when a new crisis hits. More QE will not really help, neither do more negative interest rates. There is indeed a limit for what conventional tools can do for monetary policy. Especially in the eurozone where monetary financing is strictly prohibited… The ECB will have no choice but to innovate and create new tools for itself.

Under the eurozone legal framework, and in a situation where the banking sector fails at transmitting monetary policy by creating more credits, there really is not many options left than resorting to things like ‘helicopter money’ whereby the ECB would distribute cash transfers to all citizens directly. It is clearly legal for the ECB to transfer money to household as long as the single purpose of those transfers is to lift inflation up, and that it does not go through government budgets. Billions of payments are made everyday by the banking sector. It should not take much of work by the eurosystem to make about 280 millions payments to all adults citizens in the eurozone.

Broadly designed in this way, helicopter money is clearly a legal monetary policy instrument that can be implemented without endangering the ECB’s independence.

Helicopter money must become an agreed possible option

For the euro to have a chance to survive, the ECB will sooner or later have to be able to provide reassurance that it can do something like ‘helicopter money’ tomorrow morning if necessary. Like it or not, this is the ultimate contingency plan we have now in case things go really awry.

Admittedly this would be a very bold, unprecedented move for the ECB to take. We can surely understand that the ECB is shying away from publicly discussing this option. This is why Frankfurt needs political guarantees (formal or not) by the EU Institutions and member states. The European Parliament (which the ECB is accountable to) should take the lead and signal its confidence in the ECB to innovate and move into unchartered territory if necessary to achieve its price stability mandate. This is precisely what the “QE for People” campaign (which I am working for) is trying to achieve.

Although the euro crisis is much more than a monetary crisis, the ECB and the role of monetary policy should not be forgotten in the debate on the future of euro. We cannot talk of a future of the euro so long as there will be doubt in the ECB’s capacity to address a possible new recession.

That is not to say that the ECB will fix all the problems. It certainly cannot. However it can certainly once again deliver price stability impeccably. Under the assurance of the ECB’s leadership, perhaps the whole range of needed political reforms in the EU would suddenly become far more easier to achieve, with growth and confidence being restored significantly.

Fixing monetary policy alone is not enough, especially in the eurozone. But we might realize soon enough that it is nevertheless a prerequisite for anything else. If monetary policy fails once again, can the monetary union survive?

Picture credit CC Kiefer