The dark sides of Iceland’s revival

Iceland is often portrayed as a role model for managing its economic collapse, but while part of this acclamation is justified, it should not be idealized.

Following my last post where I attributed much of the country’s revival to one specific decision to cancel 70% of its external debt, I would like to highlight here some facts that tend to show that the Icelandic story is not so beautiful.

The krona is the icelandic weakness

A lot of people think that Iceland’s recovery is largely due to its currency, the Icelandic krona. It is true that if Iceland were in the eurozone, it would have probably been more or less forced to accept a bailout deal like Ireland did. And like in Ireland, it would not have been of great help. In this regard, having its own currency was a good thing for Iceland.

However, one should be more prudent when talking about the effect of the devaluation of the krona. For instance, the spanish newspaper El Economista argues:

Should Spain follows the icelandic example ? On a quick analysis basis, several problems appear. Firstly, since Spain doesn’t have its own currency, we could not devaluate it in order to stimulate the economy and help our exportation trade.

This kind of logic reveals poor knowledge of Iceland’s story. The devaluation of the krona was not intended by the Icelandic policymakers. This was simply a consequence of the wide mistrust towards Iceland in 2008 when the banks were suspected to be insolvent. Since the collapse, the krona never returned to its pre-crisis exchange rate (that was largely supported by the carry trade on the Icelandic currency). And this is a big problem for the Icelandic economy.

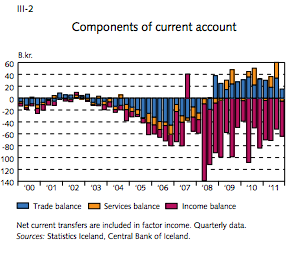

Of course, on the one hand, the devaluation is good for the competitivity of the Island in the World. And indeed, as this chart from the Icelandic central bank shows, this enabled a swing in the trade balance of Iceland, with a regular surplus since 2008 (however largely compensated by others negative flows):

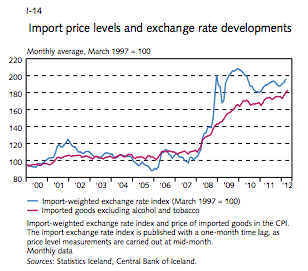

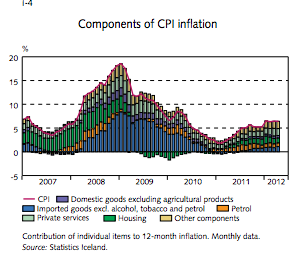

On the other hand, because it is an island, the national economy of Iceland relies a lot on imports products. In this regard, the low value of the krona is a big issue, since it increases the prices of many consumption products. Again, these two charts are quite explicit (see the blue part on chart 2):

Because of Iceland’s reliance on import products the government had not choice but to reach a bailout deal with the IMF in order to get foreign currencies.

Today, about 1000 bn kronas are believed to be owned abroad. In order to avoid further depreciation of the krona, authorities (pushed by the IMF) have adopted currency restrictions that prevent foreign investors to sell their kronas against foreign currencies. Same for ‘normal’ people: they have to ask special permission from the central bank for moving their assets abroad or invest. These capital controls are getting irksome for Icelanders, especially those who want to emigrate. But while this situation cannot stand forever, it appears that the central bank is trapped into its own strategy…

Such issues explain why there is a intense debate in Iceland about the krona. Some people argue it is time to join the euro, or even the Canadian dollar.

The mortgage deathly spirale of death

Unfortunately, that’s not all of it. Because a lot of mortgages contracted by Icelandic households (not to say almost all of them) are pegged to the inflation index or foreign-currency denominated, the purchasing power of the vast majority of People has fallen dramatically. Put it simple, indebted people are not only affected by the inflation, but also by the increase of their mortgage payments. This is a double punishment for them.

And of course, this led to a lot of defaults and financial distress situation. A recent study led jointly with the central bank of Iceland and the University of Aarhus sounds the alarm about this situation:

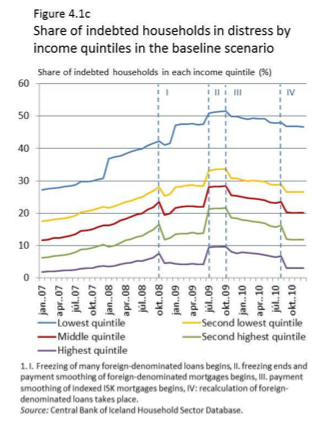

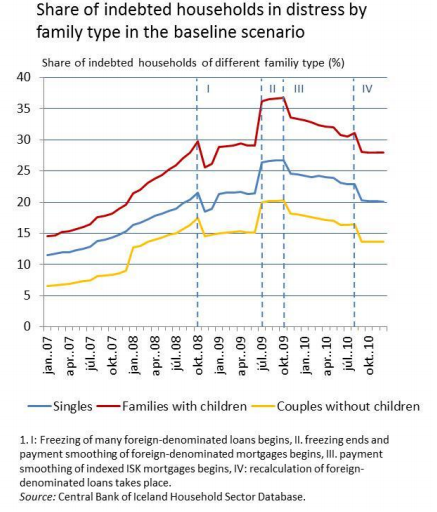

Share of indebted households in distress nearly doubled in the run-up to the banking collapse as the currency depreciated and inflation increased.

Roughly 20 per cent of indebted households are in distress at year-end 2010 compared to 25 per cent in the absence of measures

Sadly, the poorest household and families are the first to suffer from over-indebtedness:

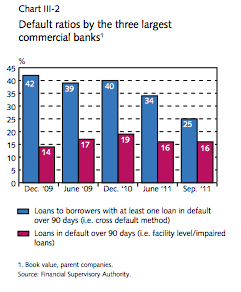

The consequences are frightening. A lot of people are in negative equity situation (their assets are valued sometimes less than 2 or 3 times the price of their credit they are struggling to reimburse), and some people are such in a bad situation that the banks are seizing their homes.

In an attempt to address the issue, Icelandic financial authorities did implement several debt restructuring measures for over-indebted people. First, the authorities suspended debt repayments on all exchangerate-linked loans. Then a smoothing scheme was put in place to reduce yields on inflation indexed loans. Furthermore, a legislative framework known as “Debtor’s Ombudsman” was erected by Reykjavík in order manage case-by-case restructuring negotiations between households and banks, with the government providing legal assistance to people. But this is a long process. To speed-up the decrease of the private indebtedness, a deal that was reached in December 2010 stipulated that any mortgage valued more than 110% of the pledged asset were to be partly written-off. The icelandic Court also reckoned some mortgage as illegal, thus leading to certain cases of debt cancellation.

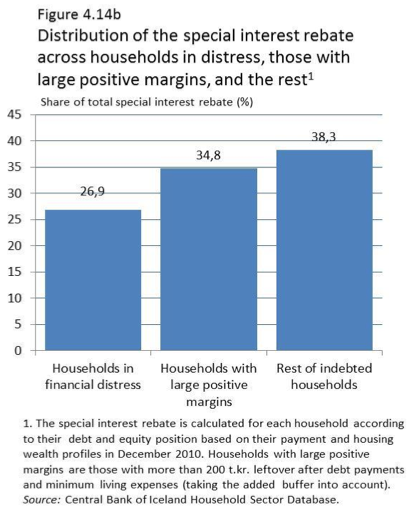

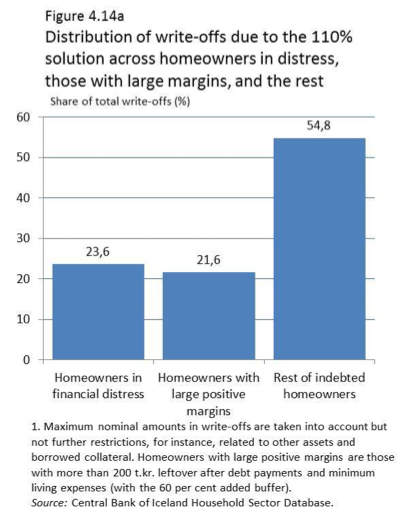

Even though theses measures were applauded by the the IMF in a recent paper, this does not sound like a “Debt forgiveness”, like some media reported last april. According to the findings of the central bank’ study led jointly with Aarhus University, these measures were not enough targeted to the most precarious people.

These data seems to tally with the general sentiment in Iceland that some rich people benefited from large debt cancellation while the poorest are left behind. Moreover, there seem to be some cases in which the banks deny to apply the Court decision on mortgage restructuring. Some people are thus claiming that further actions should be done. But it is unclear how much losses the banking system can bear.

How not to reform a banking system

Which leads me to another hard reality: the Icelandic banking system has not been much reformed yet.

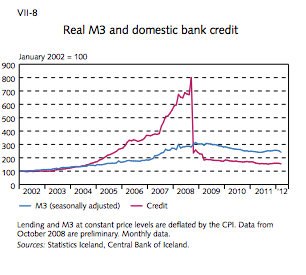

Despite of the government decision to let the major banks collapse, their nationalization, the cancellation of their external debts, and the concentration of the banking sector (there are currently 11 banks operating in Iceland compared to 20 before the crisis), the banking system is currently breaking off the potential growth of the Icelandic economy.

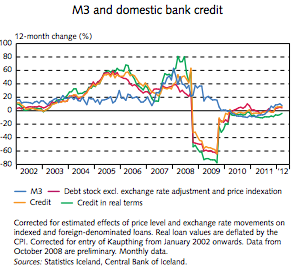

A simple look at the monetary aggregates show very little progress in the credit development in the island:

The problems are pretty clears, as Jon Danielsson explains:

The new beneficial owners of the banks treat them more as asset management institutions than providers of financial services. That entails maximizing recovery from creditors and profiting from running failed firms that they have fully or partially taken over. The banks are reluctant to write down loans, so they roll them over. The practice, known as ‘evergreening’, is more the norm than the exception.

Firms that escaped default in the crisis are at a significant disadvantage compared to worse-run competitors who failed and passed into the hands of the banks since the banks favour their own companies in access to credit. In turn, this holds back recovery and discourages investment because any new firm would have to obtain banking services from the very same banks competing against them.

Iceland’s recovery: a beautiful story?

One must admit that the Icelandic story has gone through remarkable events such as the seizing of the banks, the cancellation of their external debts, the bravour of Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson (the president of Iceland), the creation of a constituent assembly and two referendums on critical issues for the country.

Few people had any hope for Iceland four years ago when the Island was its banks collapsed with subprime bubble’s burst. This explains probably why the little recovery of the icelandic economy fuels so many fantasies on the internet.

But one have to remind that the management of the crisis in Iceland was more the result of a dead-end situation rather than a conscious “rebellion against the capitalist system”, like it is sometimes said.

Still, the very economic facts are not so shining. And many decisions could have been taken in a better manner, notably in the management of banking reforms and the restructuring of household debts.

Last but not least, tremendous challenges are still facing the tiny island. The People will soon have to decide on the destiny of their national currency, and the opportunity of joining the European Union also bears huge consequences for the country.

All in all, rather than a “beautiful story”, a more appropriate description of the revival of Iceland would certainly be : “it could have been much, much worse”…

Picture: ![]()

![]()

![]() Talba

Talba